Harold B. Franklin, president of West Coast Theaters, detailed the structure of the 1920s movie theater industry in his book, Motion Picture Theater Management. It consisted then, as it does today, of three branches: producers, distributors, and exhibitors. In that era, exhibition could be broken down further into a few types of theaters: the “de luxe first run” theaters, neighborhood theaters, and a few others, including mixed (vaudeville-picture) houses, “double feature” houses, “sensational” houses specializing in action movies, westerns, and melodramas, and so on. Franklin also noted the “Super,” or movie palaces seating 3,500 or more patrons, although few other writers use this term.1

Before the age of the movie palace, or the deluxe house, theatrical exhibition was centered around neighborhood theaters—storefront theaters owned by independent businessmen with ties to their community. There were regional chains, but on a relatively small scale. Along with Barney and A.J. Balaban, Sam Katz pioneered his movie palace strategy at Chicago’s Central Park Theatre.

The Balaban & Katz Company grew from a single theater to the undisputed king of Chicago’s exhibition industry. Its strategy was to place movie palaces in the northern, western, and southern outlying business centers, then one downtown, to draw customers from everywhere in the city. By 1926, B&K controlled 93 theaters, all in Illinois. In June 30, 1926, Adolph Zukor’s Famous Players-Lasky, one of the Big Three studios, bought a controlling interest in Balaban & Katz and hired Sam Katz and his team to continue this expansionist strategy under a new name: Publix Theaters.2

Deluxe movie theaters were by no means the rule, however, even at their prime. Of the 21,664 theaters in the U.S. in 1927, roughly 1,000 were palaces in the United States, all in cities. First- and second-run theaters (about 2,000 total, including the palaces), accounted for roughly 50% of theater admissions and 75% of revenue, so their importance to the studios—and to the motion picture theater owners—was enormous.3 Theaters had yet to significantly capitalize on concessions; unlike today, when popcorn and candy sales account for roughly 40% of a theater’s revenue, few theaters even sold popcorn. Patrons relied instead on the almost ubiquitous candy stores next door.4

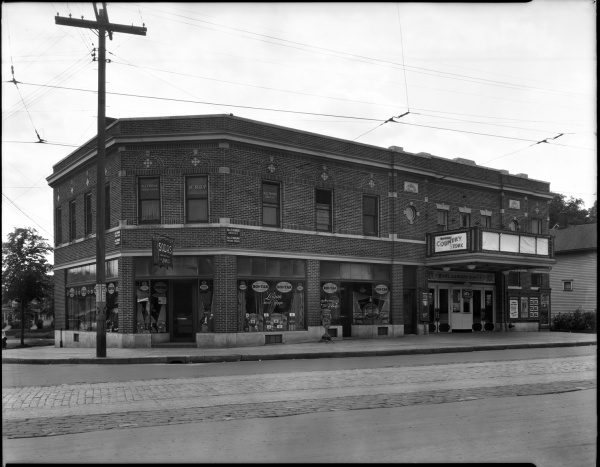

Source: Minnesota Historical Society

Evening shows at larger movie theaters in the U.S. offered “a smorgasbord of movies, live acts, and music during the two-hour show.” A typical program opened with an overture by the musicians, often playing off the score for the feature. Following this would be a live stage act, one or two comedy shorts or cartoons, a newsreel, and finally the feature film. The live presentations, as well as the first run pictures, were credited with drawing patrons to the movie palaces from the suburbs and ethnic neighborhoods, away from their own neighborhood theaters.5 In 1926, theaters employed over one-third of all full-time musicians—over 20,000 nationwide.6 Deluxe theaters would hold a movie for a weeklong engagement, sometimes holding it over if receipts warranted. Longer engagements, particularly on Broadway, generated the appearance of a hit, so theaters affiliated with the producer-distributors would sometimes artificially extend runs to promote films to subsequent run houses down the line. The largest palaces were, effectively, “show windows”—but with operating costs as high as $35,000 a week, if the feature presentation was not a box office draw, the rest of the smorgasbord had to be.7

In contrast to the palaces, neighborhood theaters would change their program two or three times per week. Many working-class people continued to watch movies at these local theaters. (In the heavily segregated Chicago, this was the norm; in Roy Rosenzweig’s Worcester, Massachusetts, his perception differed.)8 Proximity and increased cost may have been a factor, but another possibility is seen in a columnist’s rant for the Minneapolis Labor Review, about the then-new Minnesota Theater:

If I ever hear of a theater where the ushers chew tobacco, use profanity and keep in physical trim by blacking patrons’ eyes I am going to buy a season ticket and be a steady attendant. I am thoroughly fed up on the saluting, bowing, kotowing, salaaming, backward-walking, ultra-courteous young men who go through bending exercises and almost kiss the tips of my shoe strings every time my wife and I step inside a theater.9

Source: Minnesota Historical Society

With roughly 434,000 people, Minneapolis merited ten theaters seating 1,000 or more moviegoers, including the Garrick (1600 seats) and the Hennepin-Orpheum (2000 seats). Saint Paul, with slightly under 250,000 citizens, had eight 1000+ seaters, although only the Capitol in Saint Paul (2,375 seats) had over 1,500 seats.10

Thanks in part to an infusion of capital from once and future brewer William Hamm, the Finkelstein & Ruben chain maintained a “virtual monopoly” on Twin Cities motion picture exhibition. Hamm was not completely new to the movie business; he owned the Majestic, Gem, and Alhambra in St. Paul before hooking up with Finkelstein & Ruben.11 Their Northwest Theater Circuit—generally referred to as Finkelstein & Ruben or “F. & R.” in the trades—operated in Minnesota, western Wisconsin, and the Dakotas, with 42 theaters in the Twin Cities alone. A handful of small, local chains had three or four theaters apiece; the only sources of competition from the producer-distributors were the Orpheum circuit’s three theaters and the Minneapolis Pantages.

Photo: Minnesota Historical Society

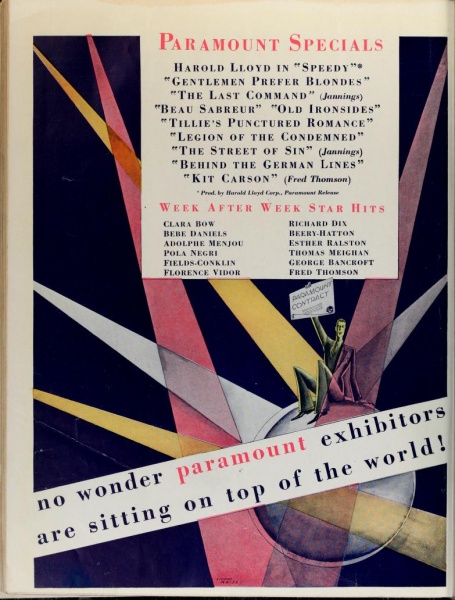

Finkelstein & Ruben was, in many ways, the Balaban & Katz of its region. While F&R had more theaters than B&K, the Chicago chain was far more powerful. Paramount’s Famous Players–Lasky theatrical arm had bought into the chain and formed Publix in 1926, hiring Sam Katz to manage its theaters. Katz’s expansionist movie palace strategy would define not only Publix but also the whole of the exhibition industry at this time. Gomery links this to the widespread adoption of chain store strategies across the U.S.12

One tactic producer-distributors used to increase profits was block booking—the bundling of popular films with lesser product to secure for their studio a larger portion of the exhibitor’s rental budget. Producers argued that it was wholesaling. Exhibitors argued that it was often used coercively, forcing them to pay for product they didn’t want.13

Another tactic was theater building or purchase. If a theater wouldn’t cooperate, the producer-distributor would buy or build a competing theater nearby, as Paramount did to Finkelstein & Ruben with the Minnesota Theater. Sometimes just the threat of buying or building would be enough to make an exhibitor or unaffiliated chain capitulate.14 Finkelstein & Ruben used this tactic at least once, in the fall of 1927. While the Minnesota Theater was still under construction, contractor William Berg hired architect Jack Liebenberg to design what would become the Granada Theater for veteran neighborhood theater managers Rubenstein and Kaplan. Finkelstein & Ruben would respond to this “invasion” with plans to convert their Calhoun Terrace ballroom into a 1,300-seat theater in direct competition with the as-yet-incomplete Granada. Berg’s theater would be “sandwiched” between the Calhoun and the Lagoon. Rubenstein and Kaplan blinked: they sold their lease to Finkelstein & Ruben, who promptly dropped their plans for the Calhoun and opened the Granada as if it were their own. It would be their last new theater.15

Through much of 1927, an eleventh deluxe theater was under construction at the corner of 9th and La Salle in Minneapolis, only two blocks away from the F&R’s State and the Hennepin-Orpheum. This new Publix theater would come to be known as the Minnesota. It was first rumored as a 2,400-seat theater in December 1926. Motion Picture News declared that it would be Finkelstein & Ruben’s “first real competition if this rumor proves true. … If competition develops in Minneapolis, there is every likelihood that it would extend to other cities in the northwest, where Northwest Theaters, Inc., controls about 122 houses. F. & R. now controls the five first-run theaters in Minneapolis, the State, Garrick, Lyric, Strand and Astor.” By the time construction began, it would grow into a 4,025 seat, $2 million “Super”—the fifth largest theater in the U.S.16

In July 1927, the regional movie trade journal Greater Amusements noted that “Paramount has already felt the sting of F. & R.’s resentment throughout the territory in retaliation for the invasion of Minneapolis, by Publix,” presumably by refusing to show any Paramount films.[0ref]Cited in “Last-Minute Hitches Block Pooling of F. & R. and Saxe,” The Film Daily, July 27, 1927.[/ref] But then Finkelstein & Ruben blinked. For whatever reason, in September 1927, they agreed to operate the Minnesota Theater on behalf of Publix, giving them 50% interest in the Minnesota and six of their Saint Paul theaters, in exchange for “preferred treatment” for Paramount’s films in all F&R theaters.17

Photo: Minnesota Historical Society

Finkelstein & Ruben would no doubt learn that, in some ways, business was worse for theaters that sold to the studio-producers than it was for the independent exhibitors who stuck it out on their own. According to Harrison’s Reports in 1931, affiliated theaters had “anywhere from three hundred to thousands of dollars a week … added to the operation as ‘Home Office Overhead’. The operating booth costs the chain not less than twice as much to operate as it did the individual owner, and in many cases as high as five times as much.”18

On July 15, 1929, William Hamm announced that Finkelstein & Ruben would sell their entire chain to the Minnesota Amusement Company, a Paramount subsidiary. Hamm was rumored to receive $7 million in cash for his share, while Finkelstein & Ruben opted for $3 million dollars of Paramount stock. The stock market would crash four months later.19

By the late 1930’s, of 450 movie theaters in the state, Minnesota Amusement owned 56 or 12%, including theaters in Rochester, Mankato, St. Cloud, Winona, Moorhead, Virginia, Hibbing, Austin, Fairmont, and St. Cloud. Those houses, however, accounted for 92% of the “first-run” theaters in Minneapolis, St. Paul, and Duluth and captured nearly 80% of the state’s total film audience.20

For all intents and purposes, Paramount–Publix had taken over the Minnesota movie theater industry. This pattern played out across the nation throughout the Depression and into the 30s and 40s. The takeover of film distribution by the studio-distributors would go largely unchecked until United States v. Paramount (1948) forced the five biggest studios—MGM, Warner Brothers, 20th Century Fox, Paramount Pictures, and RKO—to sell off their theaters and end block blooking.21