On October 6, 1927, The Jazz Singer opened in New York City. Although two Twin Cities theaters could screen Vitaphone pictures, the film that revolutionized the “talkie” would not open nationally until early 1928. It went on to gross $3.9 million nationally. The success of The Jazz Singer and Al Jolson’s even more successful, late-1928 follow-up The Singing Fool cemented the popularity of the talkie, and by 1931 Hollywood stopped making silent features almost entirely.1

As Fred Fedeli described his working-class immigrant neighborhood in Worcester, Massachusetts, some neighborhoods were inclined to hold out against the transition:

We went into the talking movies later on, and they didn’t talk any more English than I did! They liked to form their own imagination. If there was a cowboy picture with shootin’ one another, they uh, that’s it. But to understand the language… We had to go into the sound. There was no more silent pictures, so we had to go into them.” 2

The popularity of the talkie proved enough to stave off the effects of the studios’ overexpansion and the 1929 stock market crash for a short time. Gross income for the industry would reach $410 million in 1930. In 1931, income was roughly 10% higher, but with a loss of $8.6 million. In 1932, income dropped sharply to $190 million, with a huge $30 million loss. The National Recovery Administration would point to “over-expansion in the direction of seating capacity, erection of theaters at an excessive cost per seat, mismanagement within the Industry, payment of inordinately large compensation for services, and the effect of the depression upon the demand for entertainment.”3

Harold Lewis noted that some independent exhibitors believed that “the introduction of sound pictures was utilized by producers as a method by means of which to hasten their monopolization of the industry.” Despite a lack of evidence for such of conspiracy, we can be sure that the introduction of sound accelerated the independent exhibitors’ demise, especially during the Great Depression then continued to do so even after most of the majors were no longer able to buy out or build out any competitors.4 Savings from laying off musicians and stagehands were offset by the producers jacking up rental fees for sound films—often twice as much as for silents; as Robert Sklar has noted, “Between 1927 and 1929, net profits for exhibition companies went up 25 percent; for producers they rose nearly 400 percent.”5

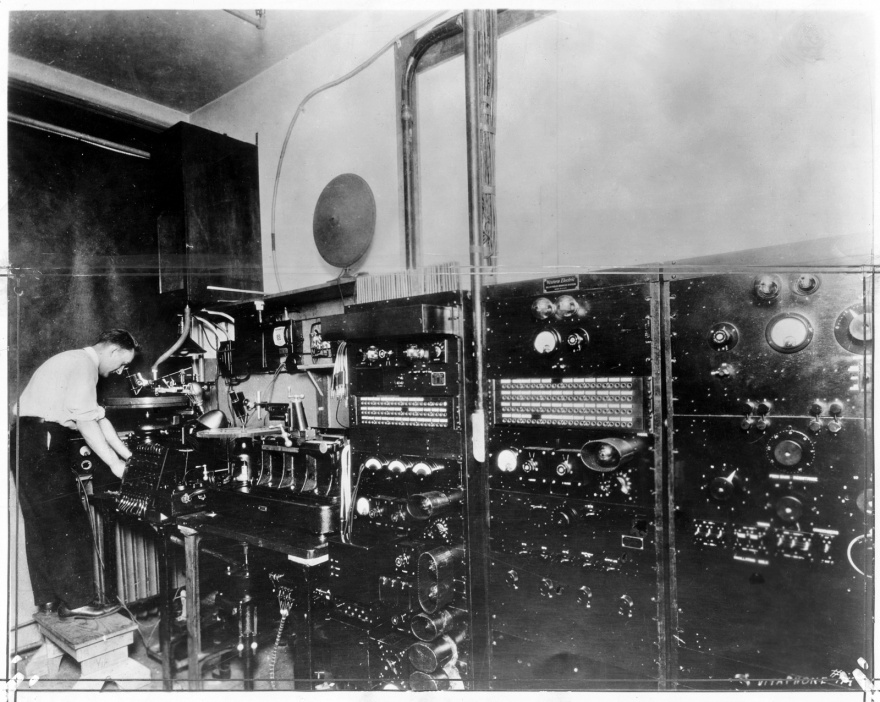

The projectionists were spared—for now—and would see their position strengthen over the next several years. Due to the complexity of the early sound equipment, use of two men per shift had become the standard at sound theaters by 1929, doubling the number of worker projectionists. The motion picture operators’ union, the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employes, saw its membership swell significantly between 1926 and 1931.6

In 1929, William F. Canavan played up this increased importance for projectionists in the theater industry. Steve J. Wurtzler writes:

In the midst of the industry-wide conversion to synchronous sound, Canavan glowingly emphasized the projectionist’s daily contribution to the cinema. Canavan labeled the projectionist both an artist and a showman, claiming that “real showmanship is one of the most essential qualities for the real projectionist.… Not surprisingly, the president of the projectionist’s union also emphasized the professionalism of the membership he represented. Canavan described an army of under-appreciated projectionists actively preparing themselves for the conversion to sound through “intensive training and study” despite inconsistent technical support from equipment manufacturers. IATSE’s members were embracing technological change despite the inherent inadequacies of both laboratory-developed equipment and “far from perfect” installations of that equipment in movie theaters.7

In the early sound era, many picture palaces, including those of Paramount–Publix, still used musicians for live shows between features, but the writing was on the wall. In the summer of 1927, Finkelstein & Ruben was already cutting four of its orchestras’ matinee performances. Variety would say that “patrons at these matinees apparently have not missed the orchestra and there have been no complaints. The organ and the Vitaphone appear to be supplying all the music desired. An electric piano attachment to the organ varies the music.”8 That September, when negotiating new contracts with the St. Paul musicians’ union, Finkelstein & Ruben opted to close St. Paul’s Astor Theater entirely rather than retain its orchestra.9

By the summer of 1928, with barely one hundred theaters actually showing talkies, musicians nationwide started getting nervous.10 The American Federation of Musicians considered the talkie a “tragic threat,” not just to musicians’ jobs but to film as an art, making cinema into a “shadow and echo” form of amusement. As film presentations (including cartoons, newsreels and shorts) became the only presentations, the need for stagehands plummeted, as well. The AFM warned, however, “If someone will justly supply a robot to operate the projection machine, these owners will install coin turnstiles at their theatre doors, and let their queer museums work while they sleep.”11 By the summer of 1929, the Minnesota Theater was the last movie theater in the Twin Cities to retain its orchestra.12

Unlike the sound transition and The Jazz Singer, there is no agreed-upon “arrival” for digital cinema. As good a date as any is the use of Texas Instruments DLP Cinema projects for the screening of Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace on June 18, 1999.13 The Motion Picture Association of America estimates that over 95% of all U.S. screens and roughly 90% of all screens worldwide are digital.14 The conversion has been far slower than with the sound transition, in part because the benefits to the exhibitor are limited: lower payroll through the elimination of a union projectionists are offset partly by higher repair costs when things can (and do) go wrong and a shorter lifespan for the equipment. In 2012, the National Association of Theater Owners estimated that 10–20% of cinemas would close; some have already done so. Independent theaters that have made the leap to digital have used loans, donations, crowdfunding campaigns, grant money, and other means to raise the $65,000+ cost.15

Although the digital transition has played out much more slowly than the sound transition, they have obviously parallels. Dominance of the exhibition industry isn’t at stake this time, but once again the owners benefits most. According to LA Weekly, “It costs about $1,500 to print one copy of a movie on 35 mm film and ship it to theaters in its heavy metal canister. … By comparison, putting out a digital copy costs a mere $150.” The cost to rent the films is the same, however—although distributors offer a virtual print fee to subsidize a portion of the purchase of digital cinema equipment. This mainly helps theaters running first-run films, however, and once virtual print fee agreements run their course, it seems as if the distributor will begin pocketing the entire savings. 35mm film will be discontinued, but no one knows when. 20th Century Fox said that in November 2012 the “date is fast approaching,” and yet film is still hanging on. Gina Disanto, president of the National Association of Theatre Owners of Pennsylvania, explained, “Nobody wants to be the bad guy.”16

With the transition to digital cinema, many theaters have phased out projectionists entirely and relegated their duties to managers or ushers—eliminating the last remaining union jobs at most movie theaters in the process.17 (A handful of theaters’ workers are organized under various unions, but these cases are exceedingly rare.) Little more than basic computer skills are needed to run a digital projector—when things work right. Of course, they don’t always. Matt Singer, writing for Criticwire (an Indiewire blog), sums up the present state of film projection:

You don’t need to pay a union projectionist period, so you definitely don’t need to pay a union projectionist overtime to stay at the theater after hours to run a midnight movie. What was once a skilled job that required training and expertise requires almost none. As one downsized projectionist said on a recent episode of American Public Media’s “Marketplace,” “My favorite quote is still the studio executive who said ‘we have a robust system and we can pay any idiot $5 an hour to run it.’”

But can any idiot run it?… Increasingly, I notice how good movies look when projected at private corporate screenings rooms and how bad movies look projected at major multiplexes—even at press screenings, where you’d think the staff would be on their best behavior. In the last few weeks I’ve seen two new blockbusters in 3D; one at a Times Square multiplex, and one at a studio’s private screening room. The multiplex blockbuster looked murky; its nighttime action scenes were basically gibberish. The privately screened blockbuster looked magnificent; even in 3D, it practically glistened, and the low-light action sequences were easy to follow.

The reason why seems obvious: the private rooms are staffed by professional projectionists, the multiplexes by unskilled employees working the “robust system.”18

Creating Multiplex, a comic strip about the staff of a movie theater, for the last ten years, during which the majority of this digital transition has taken place,19 I have become aware in the quality of film projection, and my own experiences with multiplexes are very similar to Singer’s. Scott Pilgrim vs. the World—in which music has a huge role—was projected in mono. The ZScreen (the modulator used to alternately polarize the image during 3D projection) was left in front of the projector during a 2D screening of The LEGO Movie, resulting in darkened, muddy colors for one of the brightest, most colorful animated films in recent memory, until my second complaint. The window in front of the projector was improperly cleaned for a screening of Frozen; again, a dark, dingy image. The $1000(-ish) xenon lamp was overdue for replacement for countless films, including, ironically, Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark; I’m told by one Multiplex reader that this is often intentional, sometimes, to cut costs.

I now drive thirty minutes away to see movies at a theater that I have never once had problems with. But how many moviegoers would do the same, and how many would simply opt to stay home and stream something to their bright, shiny HDTV? Undeniably, the big-budget spectacles are still draws, but with 2014 admissions at their lowest point in two decades, it seems likely that audiences are waiting for home video for a lot of films they might have seen on the big screen.20

Projection, of course, is not the only factor. Ticket prices continue to rise, and the ongoing cinematization of television continues to produce more and more product that likely appeals to frequent (or formerly frequent) filmgoers, among other factors.21 I am not arguing that the sky is falling; but movies were the 20th century art form. If the movies are to remain the 21st century art form, the movie theater industry need to be better—to present films audiences can’t see at home at standards of quality they can’t get at home, and to make moviegoing special again. I’m no Luddite. A pristine presentation of a 4K digital cinema package can be a thing of beauty—but a film presentation is only as good as the people ensuring that it is done right.